Why India doesn't export Milk?

How India organized dairy for livelihoods, not exports

Last week, India concluded its third major trade pact of the year, the India–New Zealand Free Trade Agreement. This comes after the India-UK Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement, and the India-Oman Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement earlier this year. The current government has been consistently pursuing an active trade agenda this year (Thanking Trump for making India competitive everyday).

What caught my eye came a day after the agreement was signed. NZ’s foreign affairs minister touted the FTA as a bad deal since it gave away too much and didn’t get much in return. He especially pointed out how India didn’t open up the dairy sector for New Zealand to get into.

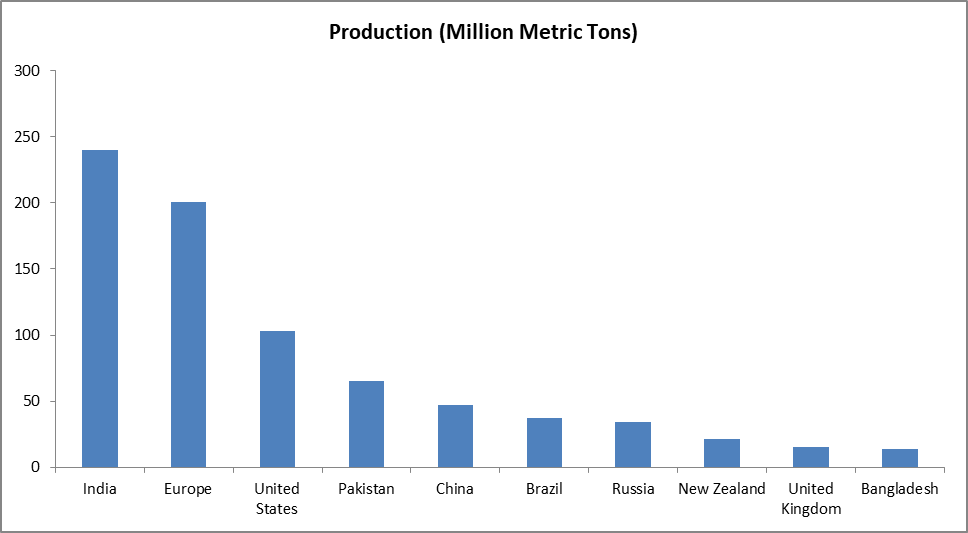

It seemed a bit surprising to me that India would be defensive to open its dairy industry since India is the world’s largest milk producer.

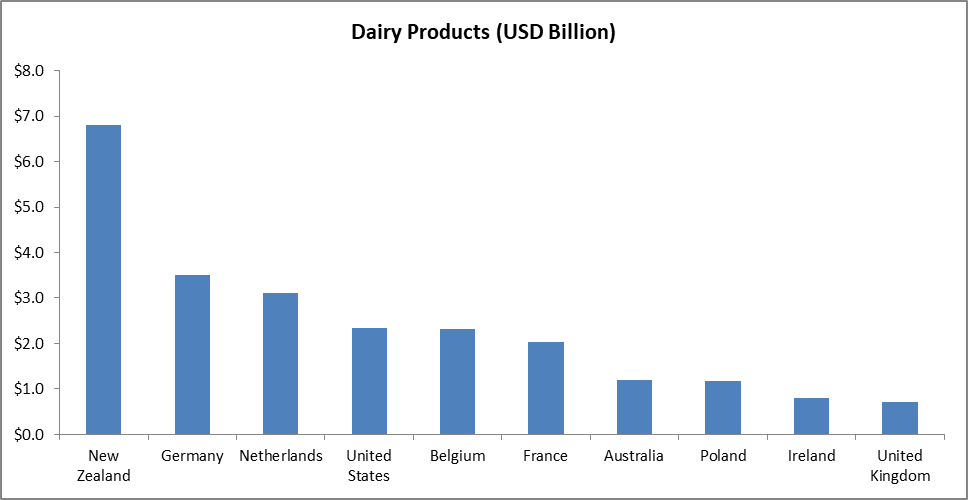

And despite production dominance, India is nowhere to be found in top 10 exporters of dairy products. New Zealand is the champion, with ~$7 Billion in exports and India stands at around $0.4 Billion.

Indians love milk

The first reason is quite intuitive. Indians love their milk. Having no exports is not for the lack of supply but the sheer magnitude of domestic demand. Unlike the major exporting regions of Oceania (New Zealand and Australia) or parts of Europe, where dairy production is largely an export-oriented commercial enterprise, in India milk is a vital component of our diets. We consume almost all of the milk that we produce.

But it is still a bit puzzling that India struggles to export even at the margin. If production scale alone were sufficient, India should be able to divert a small share of output toward global markets.

That it does not points to deeper structural and political constraints embedded in how the dairy sector is organised.

Dairy industry is a source of daily income

Nearly 90 percent of India’s milk production comes from smallholder farmers, most of whom own five or fewer animals. A lot of these farmers have crops on the side, so selling milk everyday is a source of daily cash flow and an insurance against failed crops. For them, dairy is a risk management tool rather than a profit-maximizing commercial enterprise.

In this ecosystem, milk must be collected in very small quantities from millions of geographically dispersed producers. This pushes up transaction costs and requires an extensive network of village collection centers, transport routes, and chilling infrastructure.

Doing all this is quite challenging as you can guess, but we have cooperatives for this to tackle.

What do dairy cooperatives exactly do?

Most states in India have their own dairy cooperative federations, such as Amul in Gujarat, Verka in Punjab, Nandini in Karnataka, Aavin in Tamil Nadu, and Mahanand in Maharashtra. These federations dominate milk procurement and retail within their home states.

These cooperatives are not government bodies in the formal sense. They are legally farmer owned entities registered under state cooperative laws, with milk producers as their members and nominal owners. Profits are meant to flow back to farmers rather than to the state. However, in practice, many cooperatives operate in close proximity to state governments. Senior management appointments, pricing decisions, expansion plans, and even branding often occur under significant political influence. This places cooperatives in a hybrid space, neither fully market driven nor fully state run, which has important implications for how they price milk, compete, and respond to shortages.

We will be going ahead with Amul as an useful example.

Amul does not produce milk. It aggregates it. It has created a system that could reliably collect small quantities of milk from millions of farmers, test basic quality parameters, and guarantee an assured buyer at a predictable price. So they have solved several structural failures simultaneously. They provide market access to marginal producers, reduce dependence on local middlemen, smooth seasonal fluctuations by converting surplus milk into storable products like butter and milk powder, and return profits back to farmers rather than external shareholders.

However, we have some messy politics happening here as well. Milk in India is classified as an “essential” commodity under the Essential Commodities Act of 1955. This gives governments sweeping powers to regulate its production, procurement, pricing, and distribution if they want. Governments tend to exercise this influence more directly through cooperatives, especially on consumer pricing. Private players are not immune, and could face intervention during shortages or sharp price spikes.

When demand rises sharply or supply falls, a normal market would respond through prices. Higher prices would moderate consumption and encourage producers to increase supply. But here, electoral considerations dominate pricing decisions. Governments hesitate to raise consumer prices, especially ahead of elections. When price caps remain untouched, shortages emerge. The better off consumers find alternatives at higher prices, while poorer households simply find milk unavailable.

This may not appear to be a pressing issue today, since milk availability is generally adequate. But prices, especially within cooperative systems, remain largely fixed. Milk producing farmers have limited ability to price their own product even when their costs rise. The absence of visible shortages should not be mistaken for the absence of stress in the system. For consumers, the problem remains invisible, but for producers, it is very real.

Private players offering higher prices to farmers are painted as villains for “disrupting” procurement. From an economic perspective, preventing farmers from benefiting from higher demand is counterproductive and suppresses incentives to increase supply.

This instinct to protect cooperative procurement at all costs also explains why cooperatives rarely compete with each other. Most operate within clearly demarcated territorial boundaries, often aligned with state borders. Within these regions, they face little meaningful competitive pressure. Stability is rewarded, while disruption is politically risky. Over time, this creates organizations that are excellent at managing volume and volatility, but weak at driving productivity, innovation, or cost reduction.

In that sense, cooperatives remain indispensable to India’s dairy economy, but they also lock it into a low risk, low ambition equilibrium. They protect livelihoods, but they also entrench inefficiencies that make global competitiveness elusive.

Why cooperatives rarely compete

Dairy cooperatives in India are not formally prohibited from competing with each other. But they were designed to operate within clearly defined territorial boundaries to ensure price stability and predictable procurement. Over time, this territorial logic hardened into political practice. State governments discourage cross-border competition because cooperatives are seen as instruments of food price management. Allowing another cooperative to compete risks losing control over procurement prices and consumer prices alike. What emerges is not a legal ban, but a system where competition is politically discouraged in the name of stability.

In 2023, Amul announced its plan of entering Karnataka. And it was, of course, met with stiff political resistance but it did finally enter in 2025. So did Nandini in Delhi in 2024. They are allowed to operate with some limitations as of now.

Even this limited cross regional competition can provide huge gains in efficiency, and innovation in product.

Additionally, companies like Hatsun, Heritage, and Country Delight have recently come into the foray and some tout it as evidence that private enterprise is soon going to transform Indian dairy.

But these firms operate within the same fragmented production base as cooperatives and therefore face similar structural constraints. They source milk from the same smallholders, face the same disease risks, and operate under the same price sensitivities. Their innovation lies primarily in branding, distribution, and consumer engagement, not in fundamentally altering how milk is produced.

Country Delight, for instance, targets a premium urban consumer willing to pay more for perceived quality and traceability. This is a retail and marketing innovation, not a structural transformation of the dairy value chain. Hatsun has built strong regional brands and efficient procurement, but it too must coexist with cooperative dominance and regulatory oversight.

These firms can improve outcomes at the margin. They definitely have led to some product innovation. There are a lot of high protein milk, paneer, etc in the market now and cooperatives like Amul and Mother Dairy have also started producing them now.

These are both important and natural steps for the dairy market to grow. Over time, this kind of competition could move the sector closer to genuine price discovery rather than administrative distortion.

How to make our cooperatives export oriented?

The private dairy players in India are still at a nascent stage. And with little competitive pressure from foreign players, there is very little incentive for the ecosystem to change. But if the Overton window1 somehow shifts, the solution lies in changing what cooperatives see as their role.

As mentioned before, cooperatives primarily function as buyers and aggregators of milk. This model has delivered food security and rural income stability, but it stops short of addressing the structural constraints that block exports. Export orientation requires cooperatives to move upstream from aggregation to active partnership in production.

India’s problem is low yield per animal, not lack of cattle. Cooperatives already have long term relationships with farmers, which puts them in a unique position to drive change. Instead of rewarding volume alone, they can start nudging farmers to get fewer, higher yielding animals, better feed practices, and improved herd management. Procurement premiums could be linked to productivity gains, not just fat content. This would be a difficult transition, because it means discouraging marginal production rather than absorbing everything. But it can be done with cooperatives helps out with procuring better yielding varieties.

Quality would be the next hurdle. Cooperatives manage quality by pooling milk and blending variation across millions of producers. That approach works domestically, mainly due to lack of good regulations but it collapses under export scrutiny and cost competitiveness of high-income countries. Export orientation would require separating export grade milk from the rest, enforcing compliance at the farm level, and building traceable supply chains.

Disease control presents another invisible barrier. High-income markets maintain a zero-tolerance policy for diseases. And India has an issue of both endemics (last in 2022), and pesticide and antibiotic residue. Indian dairy would remain locked out of markets until these farm-level safety standards are met.

Cost remains the final constraint. Cooperatives today are not designed to optimize costs. An export oriented approach would require dedicated processing lines, longer term contracts with farmers, and feed optimization at scale. None of this is technically complex, but it does require a corporate way of doing things.

Rather than trying to make the entire country export compliant, cooperatives could focus on specific regions or farmer clusters and apply stricter standards across the board. Productivity improvements, quality enforcement, cost optimization, vaccination, monitoring, and certification can all be coordinated within these zones. India has successfully used this model in horticulture exports. There is no reason dairy cannot follow a similar path, except for the political reluctance to differentiate between farmers.

Ultimately, like a lot of issues, the constraint is political. Export orientation requires accepting loosening state influence over cooperatives and allowing market signals to operate more freely. Until that political choice is made, cooperatives will continue to prioritize livelihood stability over global competitiveness, not because they are inefficient, but because that is exactly what they were designed to do.

Addendum: Can firms be the exporters?

India already has examples where this approach has worked.

I am sure you have heard of Sahyadri Farms.

By organizing as firms or producer companies rather than cooperatives, these farmers operated outside the logic of price stabilization and essential commodity politics. That insulation from day to day political intervention made discipline possible. Pricing, procurement, and quality decisions were not politically managed but they did get some enabling support from the state. More or less, the supply chains were market led.

Export markets were treated as the objective from the start.

Farmers were aggregated into producer companies and tightly managed clusters. Quality standards were strictly enforced, disease control became non negotiable, and price signals were allowed to flow through the system. Poor quality produce was excluded rather than absorbed.

This model does not eliminate risk but it shows that with the right institutional structure, Indian farmers can meet global standards and compete internationally.

Overton Window is a model showing the range of political ideas the public finds acceptable at a given time, from unthinkable to popular; it shifts as societal norms evolve, making once-radical ideas mainstream.

Good one as usual bhai

Indians love wheat and milk. These are essential components of an Indian household’s diet, and price stability in both is politically and socially crucial. While export orientation as a broader strategy is desirable, I am not convinced that the dairy sector in India necessarily needs it at this stage.

Some degree of protectionism is justified here. As you rightly point out, the industry is highly scattered, with no single dominant producer. Optimisation is certainly needed, but it is worth asking. Why fix something that is not visibly broken?

The supply shortages you mention may not be of the magnitude often assumed. A large number of independent milk producers still operate outside the cooperative ecosystem and continue to meet local demand. Their presence provides an additional buffer that is often missed in macro-level analysis.